BLOG

programming languages // distributed systems // music

Exploring Loop Perforation Opportunities in OCaml Programs

09 Aug 2016

Approximate computing is sacrificing accuracy in the hopes of reducing resource usage. Loop perforation is an approximate programming technique with a simple story: skip loop iterations whenever we can. This simple idea is why loop perforation is one of the simplest approximate programming techniques to understand and apply to existing programs. Computations often use loops to aggregate values or to repeat subcomputations until a convergence. Often, it is acceptable to simply skip some of the values in an aggregation or to stop a computation before it has a chance to converge.

This summer I’ve been working on a handful of projects at OCaml Labs in the pleasant city of Cambridge, UK. Part of my work has been in creating a tool for loop perforation.

Aperf

aperf

(opam,

github) is a

research quality

tool

for exploring loop perforation opportunities in OCaml programs.

Aperf takes a user-prepared source file,

instructions on how to build the program,

and a way to evaluate its accuracy,

and will try to find a good balance

between high speedup and low accuracy loss.

It does this by testing perforation configurations

one by one.

A perforation configuration is a perforation percentage for each

for loop which the user requests for testing.

A computation with four perforation hooks will have configurations

like [0.13; 1.0; 0.50; 0.75], etc.

Aperf searches for configurations to try either

by exhaustively enumerating all possibilities or by

pseudo-smartly using optimization techniques.

Aperf offers hooks into its system in the form of

ppx annotations

and Aperf module functions in a source file.

A user annotates for loops as

for i = 1 to 10 do

work ()

done [@perforate]

Upon request, aperf can store the amount of perforation into a reference variable:

let p = ref 1. in

for i = 1 to 10 do

work ()

done [@perforatenote p]

This could be useful for extrapolating an answer.

Right now, the only Aperf module function used for hooking

perforation is Aperf.array_iter_approx which has

the same type as Array.iter.

If this tool makes it out of the research stage then

we will add more perforation hooks.

(They are easy to add, thanks to

ppx_metaquot.)

Optimizing

Right now we only support exhaustive search and hill climbing. Better strategies, including interacting with nlopt and its ocaml bindings, could be a future direction.

Our hill climbing uses the fitness function described in Managing Performance vs. Accuracy Trade-offs with Loop Perforation1:

\[\frac{2}{\frac{1}{\textrm{speedup}-1}+\frac{1}{1-(\frac{\textrm{accuracy_loss}}{b})}}\]The b parameter (which we also call the accuracy loss bound) is for controlling the maximum acceptable accuracy loss as well as giving more weight to the accuracy part of the computation. In other words, a perforation solution must work harder at maintaining low accuracy loss than in speeding up the computation.

Limitations

OCaml programs don’t usually use loops.

This is what initially led us to offer Aperf.array_iter_approx

Programs must have a way to calculate the accuracy of perforated answers. This is a huge limitation in practice because usually this means the user of aperf must knowing the answer ahead of time. In a lot of domains this is unfeasible. Finding applicable domains is an ongoing problem in approximate computing.

Examples

Summation

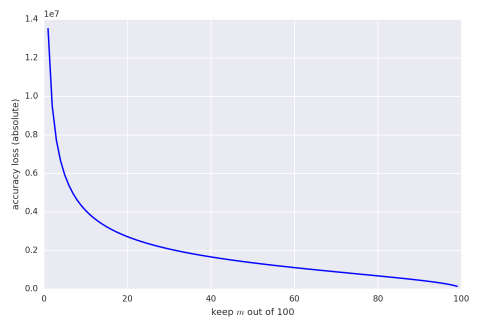

Summing $m$ out of $n$ numbers sounds boring but it’s a good place to start. This problem is interesting because there are theoretical bounds to compare results to. Hoeffding’s Inequality tells us what we can expect for absolute error. The following graph gives maximum absolute error, with confidence of 95%, when keeping and summing $m$ variables out of 100 where each variable is drawn uniformly from the range $[0,100{,}000]$.

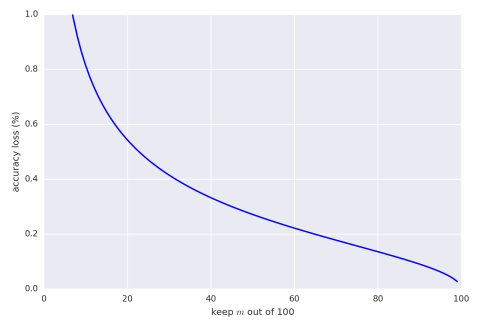

We can also give the same graph with percentage bounds (assuming the result is 5,000,000).

Our code for summing is a little awkward because aperf cannot

currently work with most computations.

The best option we can fit our computation into is

Aperf.array_iter_approx.

We also use [@perforatenote perforated] which

hooks into aperf and saves the used perforation to

the variable perforated.

We use this to extrapolate the final summation value.

The final, awkward code:

Aperf.array_iter_approx (fun a -> answer := !answer + a) arr [@perforatenote perforated] ;

answer := int_of_float ((float_of_int !answer) *. (1. /. !perforated)) ;

Training

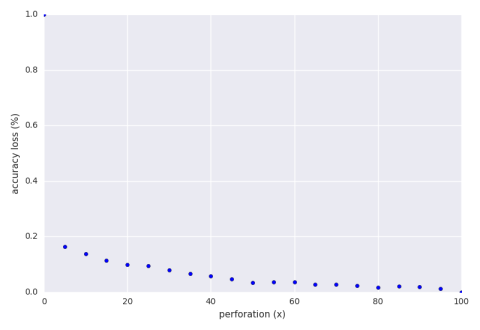

We perform initial exploration using 30 input sets of 100 numbers between 0 and 100,000. Below is a graph of the accuracy loss of an exhaustive search of perforation while keeping $x$ out of the 100 numbers.

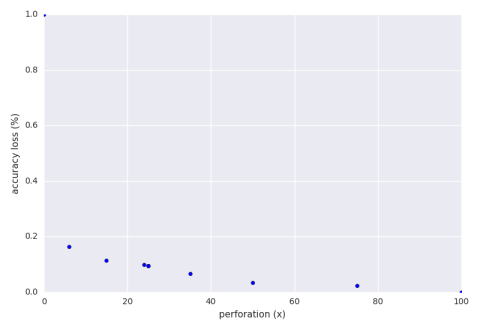

Note that we are well below the theoretical loss. Below is a graph of the accuracy loss of a hill climbing run of the perforation with an accuracy loss bound of 30%.

Our exploration finds that a perforation of 15% is adequate. This means that out of 100 numbers we are only summing 15 of them. From this we get a speedup of 3.6x and an accuracy loss of 11%.

It specifically chose 15% because it had a good combination of high speedup and low accuracy loss. Among the other configurations the system tried was 35%. It had a speedup of 2.3x and an accuracy loss of 9.5%. Why wasn’t it chosen? The program saw that with just a 1.5% further sacrifice of accuracy the system was able to decrease run time by over one factor. Another configuration the system tried was 6% which has an impressive speedup of 7.9x at an accuracy loss of 16%. The system, as programmed now, did not want to sacrifice an extra 5% accuracy loss for the extra speed. Perhaps if aperf supported user defined climbing strategies then someone could program a strategy which accepted that tradeoff and explored further.

If we require an accuracy loss bound of 5% then aperf finds a perforation of 50% to be the best result which gives a speedup of 1.3x and an accuracy loss of 3.5%.

Testing

We test the two perforation results from the 30% accuracy bound and the 5% accuracy bound on 10 testing sets each of 30 input sets of 100 numbers between 0 and 100,000. This is to test the generalization of the perforation—we want the perforation to work equally well on data it wasn’t trained for. Over 10 runs, with perforation 15% the average accuracy loss is 11.8% and with perforation 50% the average accuracy loss is 5.2%.

We then run the same experiment but with inputs drawn from the range $[0, 1{,}000{,}000]$. This is to test the scalability of the perforation—we want the perforation to work well for larger ranges of data than those it was trained for. Over 10 runs, with perforation 15% the average accuracy loss is 10.4% and with perforation 50% the average accuracy loss is 4.8%.

It looks like the perforation is generalizing and scaling nicely. Of course this is a simple problem and we’d like to explore some results from a more complex domain.

K-means

We perforate two loops in K-means

- the loop over the points when finding new centers

- the number of iterations of the step algorithm

Training

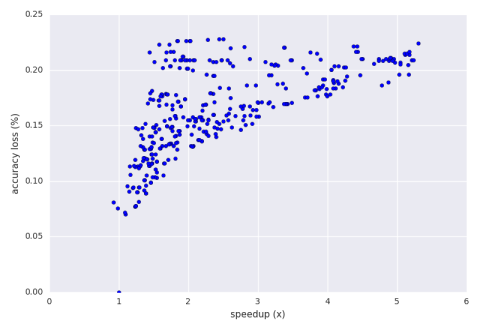

We initially train on 30 inputs of 1,000 2-dimensional points where values in each dimension range from 0 to 500. Below is a graph of the speedup vs. accuracy loss of an exhaustive search of perforation.

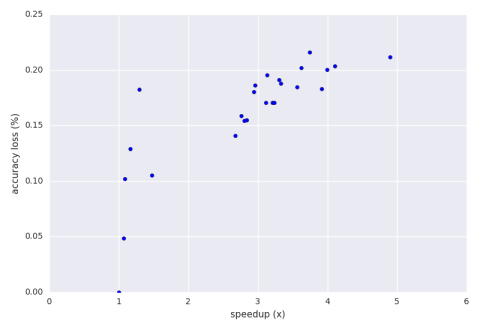

Below is a graph of the speedup vs. accuracy loss of a hill climbing run of the perforation with an accuracy loss bound of 30%.

The result aperf picked in the end was 44% perforation for the points loop and 33% perforation for the step algorithm. This configuration had a speedup of 2.8x and an accuracy loss of 15.5%. If the user wishes to move upwards into the 3x speedup range then there are some results there that offer 17% accuracy loss and above as seen on the graph. Again, this is all about efficiently exploring the perforation configuration space. Different strategies could be a future feature.

Testing

We test on 30 inputs of 1,000 2-dimensional points where values in each dimension range from 0 to 1,000. This tests whether the perforation scales with larger ranges on the dimensions. Over 10 runs, the average speedup is 2.8x and the average accuracy loss is 16.8%.

We also test on 30 inputs of 10,000 2-dimensional points with the same dimension ranges. This tests if the perforation scales with the number of points in each input set. Over 10 runs, the average speedup is 3.2x and the average accuracy loss is 14.3%.

Finally, we test on 30 inputs of 10,000 2-dimensional points where values in each dimension range from 0 to 5,000. This tests if the perforation scales with larger ranges in the dimensions as well as the number of points in each input set. Over 30 runs, the average speedup is 3.2x and the average accuracy loss is 13.0%.

The perforation seems to be scaling nicely.

Further

We should test more computations with aperf. I’m excited to see how the community may use this tool and I’m willing to work with anyone who wants to use aperf.

View on GitHub